Review of Delacave’s album Every Night Is A Moon Rising (2023)

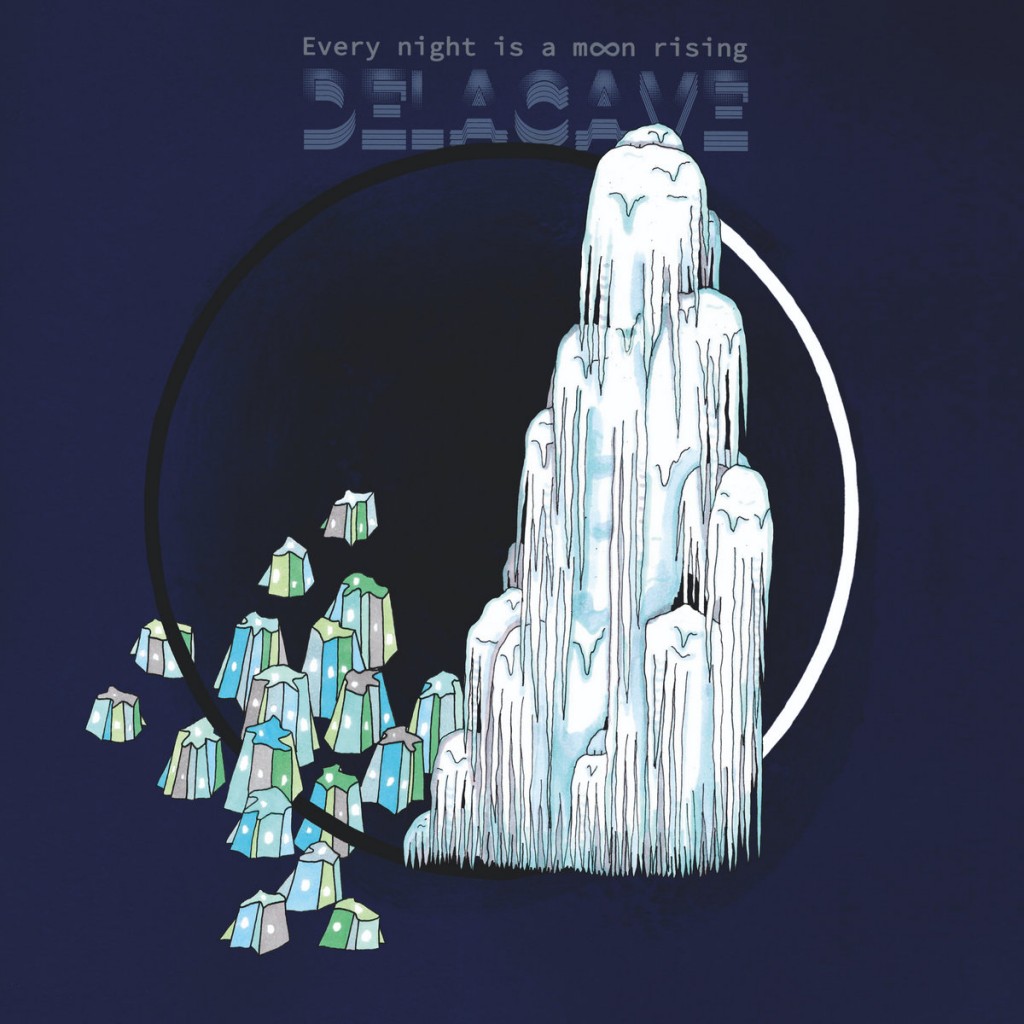

Every Night Is A Moon Rising (2023), the fourth album by Delacave, reveals that Seb Normal (synths, drums programming, and arrangements) and Liliane Chansard (vocals, bass, lyrics, and illustrations – as she is also a visual artist) are interested in people’s connection with nature. Their message now is: “every atom of our beings is nature”. Lyrics such as, “tropical bears in the white sand”, from the album’s opener Fatherless, and, “fish rise to the surface”, from the masterpiece Crossing Times, suggest that the duo, which call themselves a ‘gloom-wave’ band, are trying to give us a bigger picture of the world in which we live, with its rich variety of species that include both humans and non-humans.

Every Night Is A Moon Rising (2023), the fourth album by Delacave, reveals that Seb Normal (synths, drums programming, and arrangements) and Liliane Chansard (vocals, bass, lyrics, and illustrations – as she is also a visual artist) are interested in people’s connection with nature. Their message now is: “every atom of our beings is nature”. Lyrics such as, “tropical bears in the white sand”, from the album’s opener Fatherless, and, “fish rise to the surface”, from the masterpiece Crossing Times, suggest that the duo, which call themselves a ‘gloom-wave’ band, are trying to give us a bigger picture of the world in which we live, with its rich variety of species that include both humans and non-humans.

Chansard’s drawings also echo this message. The small, white, floating pieces of what looks like ice, on the front-cover artwork and on the inner sleeve, are ice glaciers that have been cut off from the land, as the earth’s temperature rises, and travel in the sea, where they melt away. The ghost-looking and snow-covered mountains in front of the large moon on the front-cover have started to melt, too.

So, are Delacave actually environmentalists? And if they are, do they address the impact of human activity on the environment employing clichéd claims about buying a reusable coffee cup and recycling waste, using pictures of cute birds and animals in danger of extinction, or do they use pictures from The Ugly Animal Preservation Society and their own individual agency, like members of leaderless grassroots environmental movements, away from mainstream politics (or no politics at all), to influence spontaneous action locally and at community level?

Delacave were part of an artistic collective called La Grande Triple Alliance Internationale de l’Est (the Great International Triple Alliance of the East), whose members lived between Metz, Strasbourg, Bruxelles and Rome. Seb Normal and Liliane Chansard would not only perform live together with their fellow Alliance members and collaborate in the studio, but also meet up at house parties, as they shared the same attitude to life – “a life without any form of compromise”, as some of them say. A film about that Alliance captures this in the humorous but sarcastic and ironic language of its members and in the directness and cynicism of their artistic output targeting Western consumer society.

But this humorous artistic expression is serious and not light at all, because it is critical. It is like political cartoons, also known as editorial cartoons. Political cartoons may look harmless and light at first, but their satirical content and biting humour makes people refer to them as weapons, with some newspaper cartoonists even addressing themselves as ‘hired assassins’.

Of course, Liliane Chansard’s illustrations are cartoon-like drawings. And although they may have been produced as political commentary, their use in a cultural context, as part of an artistic work that is independent of organised politics, allows greater flexibility of interpretation. Whereas editorial cartoons, whose entertainment function becomes secondary, are only understood in political terms. This single-lens reading has often made them seem unpleasant, shocking, and even offensive.

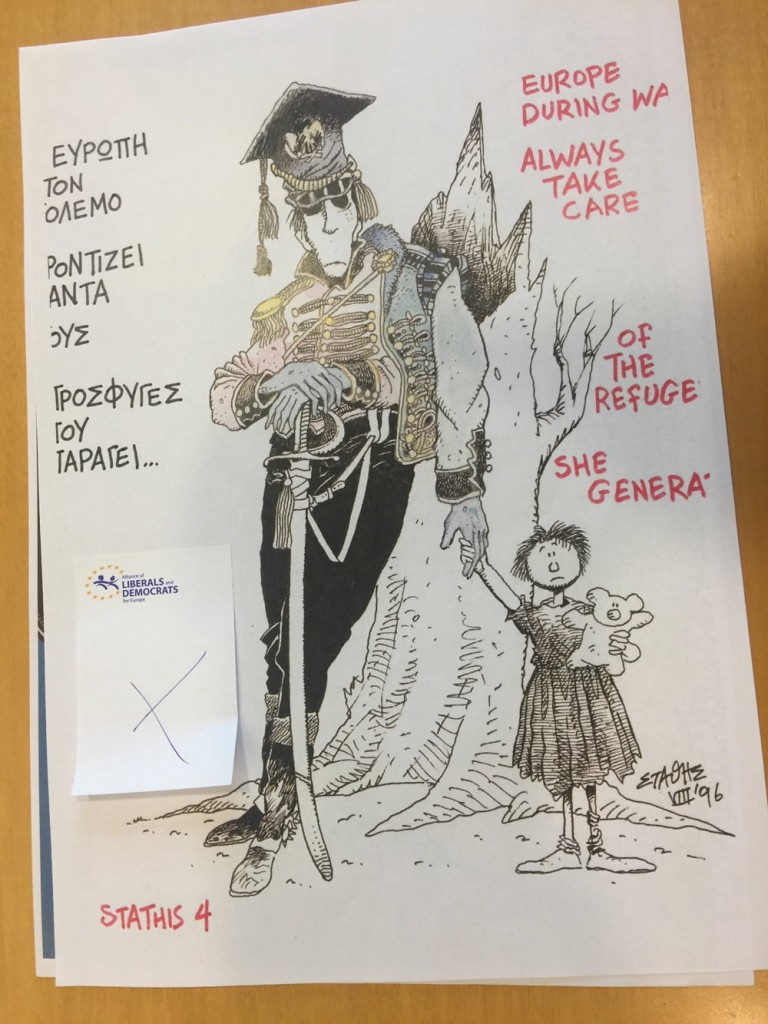

In 2017, for example, editorial cartoons were seen as offensive and were banned from an exhibition by a group of liberal politicians, an otherwise open-minded political orientation advocating democratic principles and values, such as freedom of expression, dialogue, and the rights of individuals. They were political cartoons from various Greek newspapers that had been sent to Brussels for the European Parliament exhibition “EU Turns 60: A Cartoon Party” (2017). According to the British Liberal Democrat politician who censored them, the Member of the European Parliament (MEP) Catherine Bearder, who was responsible for cultural and artistic events – before Britain’s departure from the EU, as the exhibition took place in 2017 – these cartoons included “controversial content”.

Some of them had been previously exhibited in Athens, at the 2016 exhibition ‘Sweet Europe’, which included cartoons made during Greece’s 2015 referendum on the country’s exit from the Eurozone and its 2016 UK equivalent, and they had simply been seen as critical of EU’s economic and security policies. Mrs Bearder’s rejection of these cartoons is understandable, because they undermined EU’s effort and ongoing concern to maintain an image for itself that promotes unity among member states and ideas of fairness and democracy.

One of them depicted a rag-wearing child refugee being saved by a medieval-Europe aristocrat, and its caption read, ‘Europe During War Always Takes Care of the Refugees She Generates”. This implied that EU’s promotion of a humanitarian image for itself was at least hypocritical. Dating from 1996, when war refugees came to Europe from Iraq, Afghanistan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Rwanda, and many other places, it raised questions about the root causes of war, Europe’s involvement in armed conflict, and Europe’s colonial past, to emphasise the fact that if Europe had prevented these wars, there would be no war refugees.

At the same time, militaries are not only big carbon emitters, with aircrafts, ships and land vehicles being fossil-fuel intensive, including the arms industry with its huge manufacturing capacity and the transportation of military equipment, but also cause significant environmental damage during armed conflicts, with toxic gases, oil and gas leaks, or fires. Afghans, for instance, still experience air pollution and issues with their contaminated land and poisoned water, as a result of the US military intervention there, especially with the so-called Mother of All Bombs (MOAB), dropped by the US in 2017, triggering skin diseases in people, and degradation of agricultural soils that caused food insecurity, both locally and globally. But as the speakers from the recent COP28 summit’s panel The Climate Toll of War and Peace on Climate Action said, the amount of money flowing into military operations is exactly the money needed to develop fossil-fuel free energy solutions to slow down global warming. Also, the only thing that can enable dialogue between countries, for international cooperation and global agreements that will tackle our environmental challenges, is peace.

So, it is not a coincidence that Liliane Chansard has chosen a form of graphic art for Every Night is A Moon Rising (2023) that is as critical as political cartoons. Editorial cartoons capture in naive-looking images the complex reality of political diplomacy and geostrategic agendas, and at the same time they look very simple. This simplicity is her tactic. It makes her fictional characters more real and the stories of the album believable.

The music also does this. Delacave have written sweet and simple synth melodies to blur imagination and reality and make their message convincing. And although they create bizarre and strange sounds, by drowning their synths in special effects, they use them in moderation, keeping the songs direct and unpolished. So, in the end, after the closing track, An Escape in Headlights (another masterpiece), you think their message, “every atom of our being is nature”, is straightforward and simple, and not at all complicated or difficult to understand.

Of course, our planet is a complicated system, with everything being interconnected. That’s why we keep failing to reverse the destructive trends of human-made climate change. We approach the multidimensional climate and biodiversity problems as single issues, rather than complex and interlinked with other problems. We introduce economic or technological fixes, for example, without considering their undesirable effects, as was the case with energy made from soy, which had a series of unexpected outcomes: the demand for more land to grow soy led to loss of rainforest, which resulted in both loss of wildlife and reduced ability of forests to cool the climate, the high price of soy made farmers switch to soy growing for fuel, decreasing food availability and increasing food prices, which caused food insecurity, and the transport of the biomass around the world by highly-polluting freight ships hadn’t been accounted for, either.

We are therefore told that the man-made problems facing our planet can only be tackled if we look at the world through a big-picture lens and approach it as one big system, to enable a change of values, mindsets, habits, and even systems of governance, for a wholesale transformation of society. Because apart from the so-called environmental crisis, we also go through economic ‘crises’ all the time, the massive health ‘crisis’ that we recently experienced, food and energy ‘crises’, as well as ‘migrant crises’, which is the name given by the media to the movement of displaced populations from one place to another as a result of war, interventionist regime-changes, or long droughts. All these ‘crises’ are interlinked.

So, it is probably obvious by now how Delacave’s stories compare with the environmental concerns we see on mainstream media, which use celebrity climate-activists, like Guardian-readers’ favourite, the Swedish student Greta Thunberg, to greenwash high-status politicians, who pose with them to gain people’s support and continue creating new wars, establish global banks to fund technological or economic fixes that will not work, and even finance spy operations through self-proclaimed environmentalists, who operate under the guise of environmentalism and are presented in Western media as founders of charity organisations concerned with the endangered Asiatic cheetah.

More importantly, using the term ‘crisis’, which is associated with mental stress or natural disasters and other unexpected natural phenomena, our governments and the media that support them create the impression that our current ‘crises’ are also natural phenomena that occur suddenly. This helps shift the attention away from human involvement, preventing us from seeing that, in reality, the environmental, economic, health and other problems we experience are man-made.

With albums like Delacave’s Every Night Is A Moon Rising (2023), it becomes obvious that there are some artists – not Delacave – who are deeply concerned with the environmental damage caused by human activities, and address the problem of using animal fur, for example, or consuming meat products (which is great that they point these things out), but there are also artists, such as Delacave, who do not blame people for these problems, but look at the bigger picture and put the issue in the right context, that of powerful elites controlling governments and turning people into passive consumers. Delacave’s approach is a more original form of creative environmental action, and it may turn out that it will have a more lasting impact and be more effective.

Chris Salatelis