‘Death In the Pot’: Review of the album, A Story of A Global Disease (2022), by Naomie Klaus

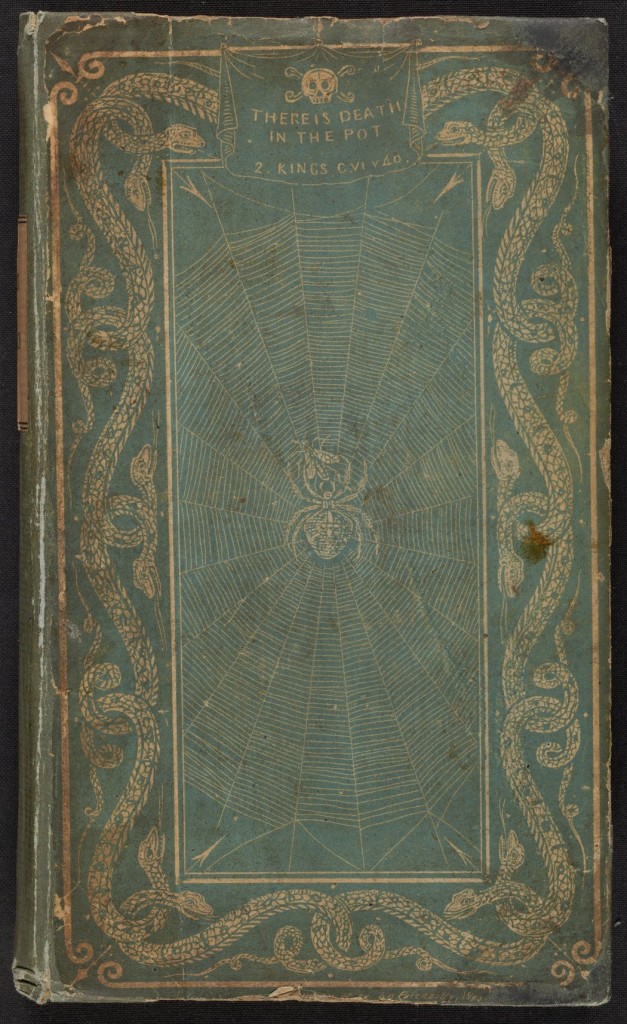

The 1820 book Death in the Pot: A Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons, by the German-born and London-based chemist Friedrich Accum, was written to help consumers detect adulterated food sold as genuine. At the time, dangerous food practices that exposed people to economic frauds were widespread in the UK market, and profit-driven business owners who sold counterfeit food as genuine used additives that contained substances harmful to health. His methods could help detect whether the tea of a particular seller, for example, was genuine or just grass, which had been laid on sheets of copper to give it a golden hue and make it look like tea. They could also help detect a toxic, bleaching additive called alum, which was used to adulterate bread and make it appear whiter, allowing the baker to spend less on whiter flour, but charge more for it in the shop.

The 1820 book Death in the Pot: A Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons, by the German-born and London-based chemist Friedrich Accum, was written to help consumers detect adulterated food sold as genuine. At the time, dangerous food practices that exposed people to economic frauds were widespread in the UK market, and profit-driven business owners who sold counterfeit food as genuine used additives that contained substances harmful to health. His methods could help detect whether the tea of a particular seller, for example, was genuine or just grass, which had been laid on sheets of copper to give it a golden hue and make it look like tea. They could also help detect a toxic, bleaching additive called alum, which was used to adulterate bread and make it appear whiter, allowing the baker to spend less on whiter flour, but charge more for it in the shop.

The album A Story of A Global Disease (2022) by Marseille-born and Brussels-based musician Naomie Klaus also relates to fake things that are made to look genuine. It is based on an idea about the Japanese Tower in Brussels and the Japanese Gardens that surround it. The Japanese Tower was constructed during 1901-1904 by orders of King Leopold II of Belgium, who had admired a similar tower, a Japanese pagoda, at an international world fair of commerce, the 1900 Universal Exhibition in Paris, and purchased it immediately. The King then asked the French architect Alexander Marcel to modify it and re-build it for him in the gardens of his Royal Palace in Brussels. When it was completed, he promised to transfer it to the nation after his death, so when he died in 1909, it was passed to the Belgian state.

The album was recorded during the recent pandemic for the project ‘On the Go’ by a Brussels arts organisation. The project invited artists to share art with the public, while restrictions were still in place, by making music to accompany walks throughout Brussels. Klaus decided to write music for a walk in the park around the Japanese Tower. Today, the Japanese Tower is administered by a public organisation within the City of Brussels authority which uses it as a museum, the Museum of the Far East. Visitors can admire not just the architecture and the surrounding gardens, but also the building’s decorative elements, including furniture and stained-glass windows, and a collection of art objects relating to the Belgian-Japanese relations throughout the years of cultural and economic exchange between the two countries.

Klaus herself describes the album as a collection of songs about ‘the artificial paradises of globalisation’. Using a range of electronic equipment to filter voice, drum-kits, and trigger synths, she expands on the idea that copies of famous cultural artefacts – like the Japanese Tower – can be enjoyed as exotic spectacles outside of the country they were made, to talk about global communication, free trade, and the problems of a consumer society. Songs such as ‘Can I Be Your Gheisha?’, ‘Crocodile Skin Shoes’, ‘Tourism Workers’, and ‘Can You Tell Me What Is Micronet?’, question the idea that the world is a tightly-woven international community with strong cultural and economic links (through international exhibitions or festivals and inter-governmental trade agreements).

During the pandemic, the word ‘globalisation’ was used by government officials around the world to mean cooperation between nations. The reality, however, was completely different, as the world is actually divided into separate nations with clearly defined borders. Governments of powerful nations competed with each other, prioritising the nation instead of the good of the humankind, and causing disagreements among them with their nationalistic decisions to buy enough vaccine supplies or large quantities of personal protective equipment (PPE) for themselves, rather than sharing them across the world.

During the pandemic, the word ‘globalisation’ was used by government officials around the world to mean cooperation between nations. The reality, however, was completely different, as the world is actually divided into separate nations with clearly defined borders. Governments of powerful nations competed with each other, prioritising the nation instead of the good of the humankind, and causing disagreements among them with their nationalistic decisions to buy enough vaccine supplies or large quantities of personal protective equipment (PPE) for themselves, rather than sharing them across the world.

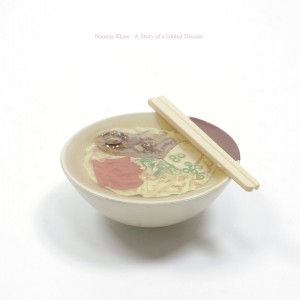

The picture of a typical Japanese dish on the album cover also reminds the argument about globalisation by the sociologists Atsuko Ichijo and Ronald Ranta, who believe that globalisation does not flatten out cultural diversity but adds more and more layers to it. For Ichijo and Ranta, the promotion of national cuisine as a brand, for example, is a form of nationalism. National cuisine offers nations a form of ‘soft power’ (unlike the military and economic ‘hard’ power) – a term used in gastrodiplomacy to mean a state’s power to enhance its prestige and appeal using its ‘traditional’ cuisine in international relations. Mediterranean cuisine, for instance, is associated with health and wellbeing, because of its nutritional value, as is Japanese cuisine, because of its association with light eating due to its use of seafood and vegetables as main ingredients. Nations are supported in this, as there are many inter-governmental initiatives, such as UNESCO’s global list of Intangible Cultural Heritage, or smaller cross-national schemes such as European Union’s Protected Geographical Status framework, which increasingly link food items to specific geographical areas. By identifying products as originated in a specific region, not allowing other countries to market them under these names, Cornish butter, Scotch whiskey, Brussels sprouts, Jersey Royal potatoes, Greek Feta cheese, Frankfurter or Cumberland sausages, and about another thousand food items, help nations exploit food’s appeal for economic growth and support the tourism industry to strengthen their private sector.

A closer look at the image on the album front cover reveals that the bowl with a Japanese soup and the chopsticks are not real but artificial. This makes it a matching image for an album about ‘the artificial paradises of globalisation’. The Belgian artist and art educator ‘Harrison’ (real name Joël Vermot), who created it and made it look like real food, encourages the listener to consider the spread of globalisation in relation to not only the McDonaldisation of the world, but also the international promotion of national cuisines in general. Taiwan, for example, who is not widely recognised as an independent state, and its territory and sovereignty are in dispute, launched an official food campaign to ensure diplomatic survival. The campaign involved Taiwanese food festivals abroad, the establishing of a Taiwanese ‘culinary think tank’, Taiwanese culinary tours, etc. By marketing Taiwan as an interesting country and enhancing its international image, the country hoped to promote its products as attractive to global consumers.

So, depending on how food is used globally, even highly nutritious recipes and genuinely healthy culinary suggestions can be ‘deleterious’ to the world’s health – to use Friedrich Accum’s term. After all, food can function like any other cultural artefact that helps shape a country’s self-image, international status, and reputation. In fact, Belgium (today the capital of the EU) had seen a number of other commissions by King Leopold II before the Japanese Tower in Brussels, that included monuments, museums, and schools, bringing him much praise, as well as the nickname “the builder king”. This effort has been recently seen as an attempt to erase from the nation’s memory (and globally) his bad reputation, because of the human atrocities committed by Belgium in central Africa during his reign. He wanted to be remembered as a beneficent ruler who gifted beautiful buildings and gardens to the nation.

This album is the 2022 release, which was made only on vinyl and in digital format. It had been made available on tape earlier, in 2021, and with a different album cover too. The tracks from the tape have now been remastered, by the Dutch producer Rude 66, and a bonus track has been added as well.

Chris Salatelis