Hidden or Invisible? – Review of Diamanda Galás’s album ‘Broken Gargoyles’ (2022)

After its appearance as a musical work in live performances in the 2010s (i.e. Dark Mofo festival, Grotowski Institute, etc.), and as an art installation in 2020 at New York’s Fridman Gallery online and in 2022 in Germany and Portugal for in-person audiences, ‘Broken Gargoyles’ was released as an album in August 2022. The album, however, is neither the soundtrack to the installation, nor a recording of the musical performance.

After its appearance as a musical work in live performances in the 2010s (i.e. Dark Mofo festival, Grotowski Institute, etc.), and as an art installation in 2020 at New York’s Fridman Gallery online and in 2022 in Germany and Portugal for in-person audiences, ‘Broken Gargoyles’ was released as an album in August 2022. The album, however, is neither the soundtrack to the installation, nor a recording of the musical performance.

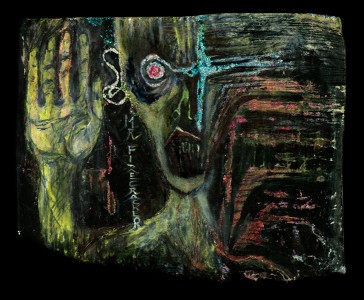

With a booklet containing illustrations of paintings, photographs and poems, Broken Gargoyles (2022) is more than a music release. Diamanda Galás has included in the booklet four illustrations of her own paintings (there were sixteen in her installation), pre-WW1 German poetry, both in the original language and the English translation, and eleven images of wounded First World War soldiers with damaged faces, taken from a 1924 illustrated book compiled and published by the German activist and pacifist Ernst Friedrich.

The reason why Galás merges these textual, visual and audio elements is that they had been used separately for years – in isolation from each other. So, with Broken Gargoyles (2022) she re-connects them. This allows her not only to re-establish the links that existed between them, but also to create new links between the historical material and some contemporary elements (her photographic portraits, taken by Robert Knoke and Austin Young, and her music). In the 2020 installation, Galás had also included film.

But the linking of all these artefacts is more of a protest against the forces that un-linked, or separated, them, and the forces that kept them apart throughout the years. In this sense, Galás engages with the separation of the arts, or the tendency to place strict barriers between different art forms. This is a widespread phenomenon in our time. We have, for example, music magazines, art magazines, poetry magazine, and so on, in which music, art, poetry, or any other art form, is discussed separately, in isolation from the other arts.

Separating the arts, and cutting off the links that exist between them, can be problematic. The arts are different forms of expression, so if we work using a single art form, we cannot provide the whole picture of a given subject. In other words, we do not tell the whole story to our audiences.

This is because information is transmitted to the brain through sensations coming from various sources. And it is our sense organs that are responsible for passing knowledge to us, when a number of different material properties are absorbed by them, as the modern Greek philosopher Helle Lambridis (1896-1970) shows in her book on the ancient Greek philosopher Empedocles. But each of our senses, she writes, receives only a limited number of information, because different stimuli activate different senses. Our eyes, for instance, cannot perceive sounds, because the information carried by audio particles in the sound is destined only for the ears. Therefore, to acquire full knowledge of something or someone, we need to receive information from many different sources.

The fact that Broken Gargoyles (2022) is primarily about the separation of the arts is not easy to spot. To understand this, we need to think of separation – or isolation – as the act of making something invisible. When we separate, for instance, two identical twins, and present only one of them, the other twin becomes ‘invisible’. We can also say that we ‘hide’ the second twin.

The first clue that leads to this conclusion exists in the music. The fact that Galás decided to recite early twentieth-century expressionist poetry in the original expressionist style, which is a form of singing that sounds almost like reading, makes Broken Gargoyles (2022) automatically an album about invisibility. Expressionism is associated with ‘social isolation’, because of the alienation from society that was experienced by expressionist artists, musicians, architects, photographers and choreographers in Germany, after the government ended up prohibiting by law the expressionist style in the early 1930s, a policy that condemned expressionist artists to invisibility until the end of the Second World War.

Then, Broken Gargoyles (2022) is based on poetry about isolation and alienation. Galás uses poems by the German expressionist poet Georg Heym. One of them, Das Fieberspital (1912), offers a rich imagery of isolation and horror in a German hospital ward with yellow-fever patients. And another, Der Dämon der Stadt (1910), contains a frightful experience of alienation in heavily industrialised and densely populated German cities. This poem describes people’s separation from nature and their locking up in apartments full of toxic air from factory fumes that cause nightmares and other physical and mental suffering.

Galás sees parallels between the isolation in Heym’s time, as experienced by the yellow-fever patients or the suffocating city dwellers, and the isolation experienced by the elderly residents in nursing homes, who were also shut out of the community during the recent pandemic, by being cut off completely from their friends and relatives. But the recent forced separation of the uninfected from the infected attracted Galás for its twisted turn. In New York nursing homes were forced to house post-ventilation and still contagious COVID-19 patients, and this fact was hidden from national media, as well as from the families and relatives of the vulnerable over 70-year-olds who lived there. So, Heym’s poetry provides the perfect metaphor to introduce the listener to the idea of hiding something to make it invisible to others.

Similarly, hidden from public view were also Friedrich’s photographs of wounded soldiers with damaged faces. The “war-damaged face was incompatible with the image of heroic self-sacrifice” and it had to be kept hidden during the war; disfigured soldiers were concealed, through ‘the institutional and social isolation of “facial” patients’, to make them invisible in the wartime press and propaganda. As a pacifist and a conscientious objector, Friedrich used these pictures in his book War Against War! (1924) to counter misinformation in the media that hid the horrors of the battlefield to suppress the negative impact of war. In other words, they helped him uncover the colonial, imperial, and indeed capitalist motives behind every war.

Lastly, the album booklet includes four of Galás’s paintings. Are these paintings hidden in the booklet? The answer, of course, is ‘No’. They have been placed prominently next to Friedrich’s photographs, which themselves are central to the album’s concept, as well as the album’s title: ‘Broken gargoyles’, Galás says, was an expression used during the First World War to “describe soldiers who were facially mutilated by skin-melting gases and machine guns, both of which were introduced during this war.” In fact, to make more apparent the link between her paintings and the photographs of wounded soldiers, Galás inserts between them her own photographic portraits. In the 2020 installation, the paintings had been juxtaposed with moving images from San Diego (where Galás now lives) that she had filmed herself during the pandemic and between lockdowns. Because those moving images had been made in a time of forced inactivity for those working in the cultural sector, they evoked the ‘wounded soldier’ who becomes inactive after injury, returns home, recovers, and then goes back to the battle (as was the case with injured soldiers, who often had to undergo surgeries and treatments in order to be sent back to the battlefield). The paintings, therefore, encourage parallels between Friedrich’s wounded soldiers and today’s artists.

At the same time, photographs of injured soldiers had to be used in medical records because wounded servicemen needed them in applications for disability payments. Soldiers were dependent on such photographic records, as they were the most valuable proof to collect a pension.

Galás’s paintings also relate to her own situation at the time of their production. In this sense, the specific dates they were made can be important as well, apart from their subjects or materials. Having begun painting in 2003 during her residence at the Civitella Ranieri in Italy, the production of paintings became more systematic in the late-2000s, a period of many changes in the music business. In the early 2010s, Galás felt dissatisfied with her then record label, Mute, rejecting a new record contract with them. Also, her back catalogue had been sold to major record companies, which equally did not seem the right record labels for her to work with, and refused to sign a deal with them, too. But while this halted her recording plans (temporarily, as Galás soon started releasing her music through her own label, Intravenal Sound Operations, and also acquired the rights to all of her work), her ideas found expression in her paintings. As Galás has stated, the ‘subject material’ of her paintings is also part of the working material of her musical projects – they are ‘simply different treatments of similar subjects’. So, while she continued composing and performing musical works as usual, the period of changes in the way she released her music allowed a different medium to become an equally important means of expression for her: painting.

And this is where Galás’s protest against the separation of the arts begins.

Unlike Friedrich’s precise close-ups, Galás’s paintings depict schematically drawn figures, whose calculated simplicity leaves facial features unresolved. Her rushed brushstrokes and thickly applied coloured pencils blur and fragment the faces, rather than defining them clearly. In the 2020 installation, Carlton Bright’s animation effects and re-colouring had blurred them even more, transforming them into interesting shapes and colour combinations.

In a 2016 article about ‘women in horror’, some of Galás’s paintings were even understood as quite pleasing, and the characters depicted in them as playful and interesting. Described as ‘tribal’ – and not strictly ‘dark’ or full of ‘horror’ – they were linked to ancient rituals. But ‘tribal’ is also another word for folk and colourful art, as well as another way to describe something humorous and amusing.

Similarly, in a short interview in 2014, Galás’s paintings are seen both as ‘twisted, horrifying, brutal and tantalizing’, or ‘designed to freak you […] out’, and as ‘amusing’, and even joyful. As Galás herself reveals in this interview, she believes that her paintings are not necessarily sad or depressing. She says, “sometimes the visual work [that I do] is actually funny, and I enjoy that.” One of the paintings used in the installation Broken Gargoyles (2020), for example, Teeth of the Sun (2014), showed a character in a state of sarcasm, with a sardonic smile revealing a sinister intent, as if it was an actor in a bitter satire.

So, Galás uses some of her paintings to introduce a mood which seems almost the opposite of Friedrich’s unpleasant and shocking photographs. The joyful colours and playful mood of the paintings disturbs the atmosphere of horror and tragedy in Heym’s unsettling poetry. After all, mood, atmosphere and emotional reaction are part of an aesthetic experience, and just like material properties, they also provide some kind of historical evidence.

And there are also elements in the music that contain moments of laughter: Galás’s vocals in the track ‘Mutilatus’, for example, culminate in a deep and convulsing chuckle (at 15:43). Heym did not indicate how his poem would be read, nor what kind of music it had to inspire, if any at all. It was Galás’s choice to do all this and to burst in a laughter at that moment.

It is possible, then, to say that this album was designed specifically to oppose the separation of the arts, as every element of it demonstrates the immense power of blending audio, textual and visual sources, and with completely different attributes and behaviours, which range from grinning grimaces and ironic facial expressions to sarcastic sounds and horrifying stories.

Unavoidably, the separation of the arts has a negative impact on artists. Artists are separated form each other when they are put into categories and often treated separately: fine artists, musicians, dancers, filmmakers, and so on. Galás, for instance, is treated by the press – and some scholars – as a composer and performer, despite the fact that she has been painting for the last twenty years, and that the staging of her performances is often designed by her.

But today, many artists are treated by the press as single-medium artists. Ruth Ewan and Jeremy Deller, for example, two visual artists who use very often music in their works, are very rarely included in the music press, as they are not considered ‘musicians’. There are also historical precedents of cultural practitioners, such as Henri Michaux, Oscar Kokoschka, Hermann Nitsch and others, who kept switching between art, theatre, literature, music and other arts, but who have not been recognised as multi-media artists.

This is also the reason why Empedocles is treated simply as a philosopher and not as a poet, too. Empedocles wrote his philosophical works in verse, to be read like poetry. And for this reason, his works were able to pass to their audiences many different information at once, because his texts’ rhythmic patterns, as well as their sounds (from reading them aloud), produced additional material properties that created mental images, heightened emotions, and so on. But we never remember Empedocles as a poet, do we?

- Chris Salatelis

Diamanda Galás, Untitled (2010)

Diamanda Galás, Untitled (2010)

All paintings © diamandagalas.com